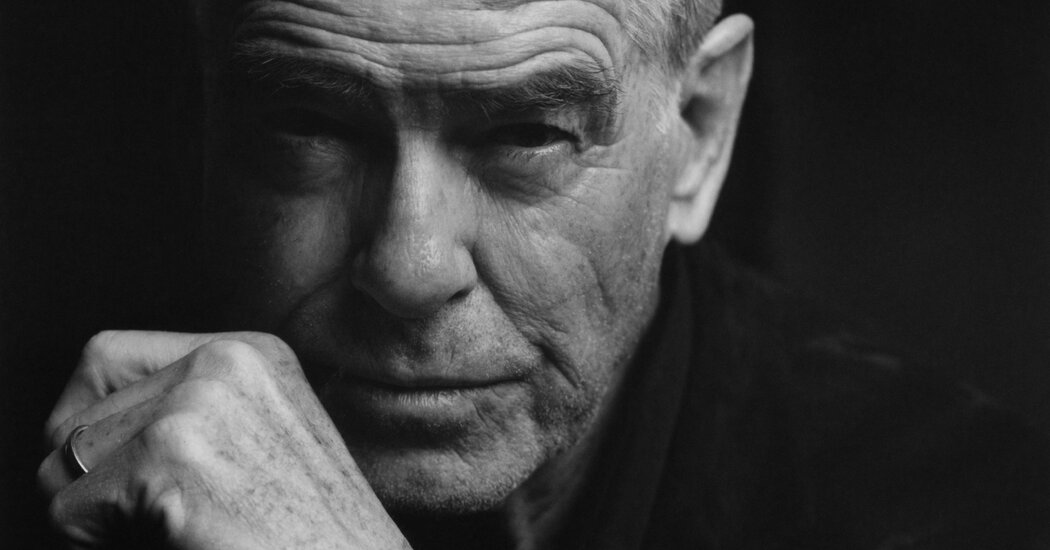

On the last day of March, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, fans approached the actor Pierce Brosnan every few minutes. Some addressed him as Mr. Brosnan, some as Mr. Bond, a reference to the four James Bond movies he made in the 1990s and early 2000s. (Brosnan has a face that demands honorifics.)

Dressed in chic monochrome — navy trench, navy pants, a navy ascot at the neck of a navy shirt — he was gracious with them all, if lightly evasive. (And yes, he is the rare man who looks plausible in an ascot.) At 71, he doesn’t often show the whole of himself. People see what they want. Mostly they see Bond.

“They miss a lot,” he said. “But it’s not up to me to show a lot. It’s not up to me to do anything but be pleasant.”

There has always been more to Brosnan than meets the eye, although what meets the eye is obviously very nice. “He is very fortunate in the genes department,” said Tom Hardy, his co-star on the new Paramount+ gangster series “MobLand” said. Brosnan refers to it all as “the Celtic alchemy.”

A longtime painter and art enthusiast, Brosnan counts “The Thomas Crown Affair,” a 1999 art heist caper, as the favorite of his movies, mostly because he got to keep the paintings. So when promotional duties brought him to New York — he splits his time between Malibu and Hawaii — he squeezed in a museum visit.

On arrival, he found the Guggenheim spiral closed for installation. (“That’s boring,” he said mildly at the ticket counter.) He contented himself with the works on display. “I love color,” Brosnan said, admiring some canvases by the Brazilian painter Beatriz Milhazes. “Exhilarating. Captivating.” His speech has a casual lyricism — he’ll rarely use a single adjective when two or three will do — but he seemed to mean it.

In his acting career, Brosnan’s palette has been fairly particular. “It’s been part of my story as an actor,” he said. “Playing the hero, playing the mysterious man, playing the man that you trust.” But his recent roles (and some that he has taken before: “The Matador,” “The Tailor of Panama”) complicate that persona.

Conrad, the criminal boss he plays in “MobLand,” harbors brutality underneath his gentlemanly wardrobe. Arthur, the British spy chief he animates in Steven Soderbergh’s sleek espionage thriller “Black Bag,” now in theaters, has his complications, too. And yet, Brosnan is still and always Bond.

“You really can’t get away from it,” he said. Which at least partly explains why, half an hour into his visit, Naomi Beckwith, the Guggenheim’s chief curator, came to offer him a tour of the installation in progress. Then she introduced him to the artist behind it, Rashid Johnson.

“I’m a fan of yours,” Johnson said. “You were my Bond.”

They chatted about art for a while. In 2023, Brosnan, who worked as a commercial artist in his teens, had his first show, “So Many Dreams,” at a Los Angeles gallery. He told Johnson what he liked about painting as opposed to acting: “The innocence of it all and no expectations.” Then he said goodbye. “Be bold,” he urged Johnson.

Walking out, Brosnan admired a Bonnard, a Cézanne, several Picassos. He clocked a Kandinsky from all the way across the room. “Just makes you want to paint,” he said. He has fantasies of moving to Paris and apprenticing with some artist in an atelier. But he isn’t ready to give up acting.

“It’s a drug now,” he said. “I need it.” Though Brosnan is often very funny (“He’s got a wicked sense of humor,” Hardy said), it wasn’t clear that he was joking.

Certainly he hasn’t quit yet. He shot his role in “Black Bag” on a quick break from another film, “Giant.” He began work on “MobLand,” in which he stars opposite Helen Mirren, just after wrapping the movie “The Thursday Murder Club,” also opposite Mirren.

“Black Bag” returns him to the secret service. His character is a spymaster of oblique motivation. The movie plays homage to classic espionage films, which made Brosnan an attractive choice for the role.

“There’s a knowingness that is shared with the audience that’s very pleasurable, a shared secret,” Soderbergh said.

Brosnan knows this, too. “I was trusted to bring them in, to engage with the audience and then to dismantle that persona,” he said. (A further bit of dismantling: He asked Soderbergh for a mild prosthetic for his nose, which sharpens his face).

He plays a similar game in “MobLand,” created by Ronan Bennett (“Top Boy”) and directed partly by Guy Ritchie. Conrad seems the consummate gentleman, but he’s not above kicking a man when he’s down — and wounded and bleeding from the mouth. As his wife, Maeve (Mirren) says, he is, beneath his dapper tweeds and Barbour, “a stone-cold Paddy killer.”

Brosnan’s portrayal makes that brutality engrossing. “He has what they call ‘spell,’” Hardy said. “He casts a spell on the room.”

This is true of Brosnan offscreen as well. His gallantry is profligate, effortless. In our time together, he held doors, he helped me with my coat, he called me darling. I knew I was being charmed. I was helpless to it. To spend these hours with him was to feel rammed by a tractor-trailer of sheer charisma.

And of course, I love Bond, too. When I wondered aloud why someone like me, who doesn’t typically enjoy gun-forward films, should feel so drawn to the character, Brosnan looked at me wryly. “Sex,” he said. “Sex. Sex. Sex. Love. Lust. Desire. Sex. That’s just it. Own it. Enjoy it. Don’t worry about it.” (Asked about the sale of the Bond franchise to Amazon earlier this year, he was more circumspect: “I wish them well.”)

This version of Brosnan — the curated wardrobe, the way he politely asked to have his lunchtime Chablis cooled (“Give it some good ice, please,” he said) — seemed authentic to him. “I love clothes; I love style,” he said. “I love the beauty of life, of men, of women. The art of life, it feeds me.”

But it is also a pose he has perfected over the years, one rooted at least in part in a childhood in Ireland that included abandonment by his father and a long separation from his mother.

“I wanted to be an artist; I wanted to be a painter,” he said. “I had no qualifications. I was really behind the eight ball — without a mother, without a father.” But that freedom allowed him to create, he said, “this persona for myself called Pierce” that has become only more refined with wealth, fame and the realization of his artistic aspirations.

Pierce is arguably his greatest role and he has little ambivalence toward it or the celebrity it has afforded him.

“I wished it; I wanted it,” he said. “So I get on with it.”

Still, he admitted, he was looking forward to the week’s end, when he could be himself, not show himself. But what he shows, in person and onscreen, it’s enough. For him, and maybe for the rest of us.

“I’ll keep playing it as long as it goes,” he said. “It got me this far. I’ll keep marching on.”