Watch out for Richard Roma. Top man among the bottom feeders at a scammy Chicago real estate agency, he has a hypnotic come-on and a dizzying spiel. Identifying your vulnerabilities with forensic accuracy, he’ll lance them with a blunt needle. (“You think you’re queer?” he asks one mark. “I’m going to tell you something: We’re all queer.”) If it’s what you need, he’ll be the brother who thinks big on your behalf, who sees beyond your sad habit of safety to the rewards only risk can offer.

Not that there are actually rewards. The lots he’s selling in Florida, in developments ludicrously called Glengarry Highlands and Glen Ross Farms, are worthless.

Back at the office, too, he’s the alpha among losers. On the leaderboard of recent earnings, he stands closest by far to the $100,000 mark that will win him a Cadillac in the agency’s sales contest. (The two lowest earners will be fired.) His colleagues are merely additional marks to be bamboozled. They have schemes; he has juice.

No wonder he remains, 41 years after he first hit Broadway in David Mamet’s “Glengarry Glen Ross,” one of theater’s greatest characters: the unregulated id of sociopathic capitalism. He makes Willy Loman look like a softy. This salesman will never die.

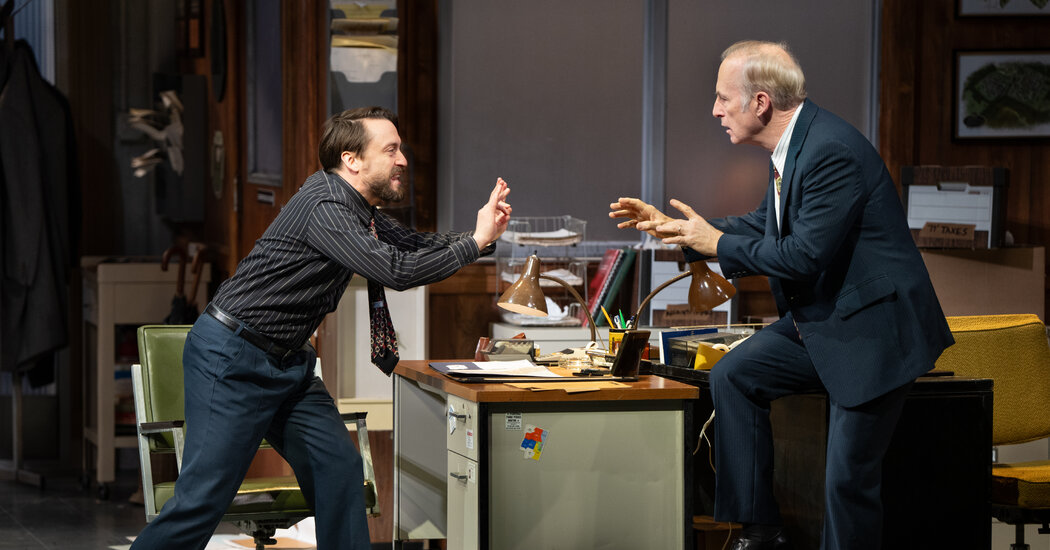

Or so I thought. But in the weirdly limp revival that opened on Monday at the Palace Theater, something has flipped. As played by Kieran Culkin, leading a sales team that also features Bob Odenkirk, Bill Burr and Michael McKean, Roma is no longer the master of everyone else’s neuroses; he’s neurotic himself. Especially in the scene that ends the first act, as he winds up for a pitch into the soul of a schlub, he is so deeply weird and interior that any semblance of a confident exterior evaporates. The man couldn’t sell a dollar for a dime.

Chalk this up to casting that confuses the flippant charm of Culkin’s usual characters, like those he played in “Succession” and “A Real Pain,” with the will to conquer that’s needed here. It takes highly honed theatrical skill to project dominance to the back of a big house for long stretches. (In previous Broadway productions, Roma was played by heavyweights: Joe Mantegna, Liev Schreiber and Bobby Cannavale; Al Pacino played him in the 1992 movie.) Culkin, whose only previous Broadway outing was as a petty drug dealer in the 2014 production of “This Is Our Youth,” has the charisma but not the steel. Long before the end of the eight-minute monologue that’s supposed to be his big aria, he wilts.

The same could be said of Patrick Marber’s staging in the overscale Palace, not usually a playhouse. Even with the balcony closed, the actors must work very hard to be heard, as Mamet is no fan of microphones. (No sound designer is credited, but a vocal coach, Kate Wilson, is.) Nor is it just the theater that’s too big; inevitably, to fill it, so is the scenic design by Scott Pask. The Chinese restaurant that’s the setting for Act I, in which no more than two people are onstage at a time, could hold a glamorous party for 100. “Glengarry” wants grimy intimacy, or at least the illusion of it.

But at whatever scale the play is done, Mamet tests a director’s mettle with his daring construction. The Chinese restaurant scenes, three in a row, each introduce, with no explanation, two new characters in medias res. First we get Shelley Levene (Odenkirk), the salesman currently in last place on the leaderboard with a total of zero, and John Williamson (Donald Webber Jr.), the manager in charge of the all-important leads. Levene tries begging and bribing for better prospects, but Williamson is unforthcoming.

Next are Dave Moss (Burr), in second place, and George Aaronow (McKean), far below in third. The contrast between them is startling: Aaronow, agreeable and strait-laced, seems resigned to the dog-eat-dog workings of the system; Moss, a hothead boiling with envy, is hellbent on subverting it. With elaborate indirection, he tries to trap Aaronow into a plan to rob the office.

Then comes the scene, meant to be the Act I climax, in which Roma buttonholes his mark, James Lingk (John Pirruccello). But by now the play has lost so much momentum that even if Culkin were Pacino, he’d be stuck at the bottom of a bag. This is to some extent the result of Marber’s fidelity to Mamet’s minimalist ethos. The clumsy blackouts that end each scene are no more dramatic than setting your phone on sleep. (The otherwise good lighting is by Jen Schriever.) Nor does any music cover the transitions; you can feel whatever energy has been laboriously ginned up draining away in the dark.

If Mamet prefers his own music, fair enough. Has there ever been dialogue as piquant and polyphonic as his? Shaping melodies out of rants and obbligatos out of expletives, he creates character from the sound not the meaning of his words, which are in any case mostly variations on the same few four-letter favorites.

You can hear that music intermittently in the first act, especially when Odenkirk and McKean, in separate scenes, find their rhythm. Both actors have been, among other things, comedians — but that’s also true of Burr, who is working too hard at being sweaty and nervous.

In any case, everyone improves in the second act, when the action shifts to the ransacked office and all the characters (plus a policeman played by Howard W. Overshown) are in play. With less weight on their shoulders, Burr and Culkin relax; Odenkirk and especially McKean shine.

I wonder whether that reflects a change in the way “Glengarry” resonates in 2025. In 1984, the play gave memorable shape to a growing understanding that the underworld of sleazy small business was merely a microcosm of the bigger, more polite variety. It suggested the way social Darwinism lay at the root of our economic system, with its zero-sum games and dominance pyramids. There’s a reason Mitch and Murray, the owners of the agency and creators of the contest, are never seen, like golden-parachuters or two-bit Godots.

It also says something that the play is dedicated to Harold Pinter, whose thug fantasias (“The Caretaker,” “The Homecoming”) trod this dramatic territory first. Now, in part thanks to the cultural power of “Glengarry” — as well as Mamet’s “American Buffalo,” which opened on Broadway in 1977 — both men’s ideas have become conventional in the process of being overtaken and one-upped by reality. The whole world, many feel, is now a consortium of thugocracies, some even sanctioned by popular acclaim. In that context, two-bit players are too puny to worry about, and greed at the scale of a Cadillac unremarkable.

So it’s not just because this is such a patchy production, or because Odenkirk and McKean are nevertheless so good in it, that the losers make the biggest impressions. The winners, once glamorous, now have nothing new to show us. Whether in desperation or dignity, the defeated now do.

Glengarry Glen Ross

Through June 28 at the Palace Theater, Manhattan; glengarryonbroadway.com. Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes.