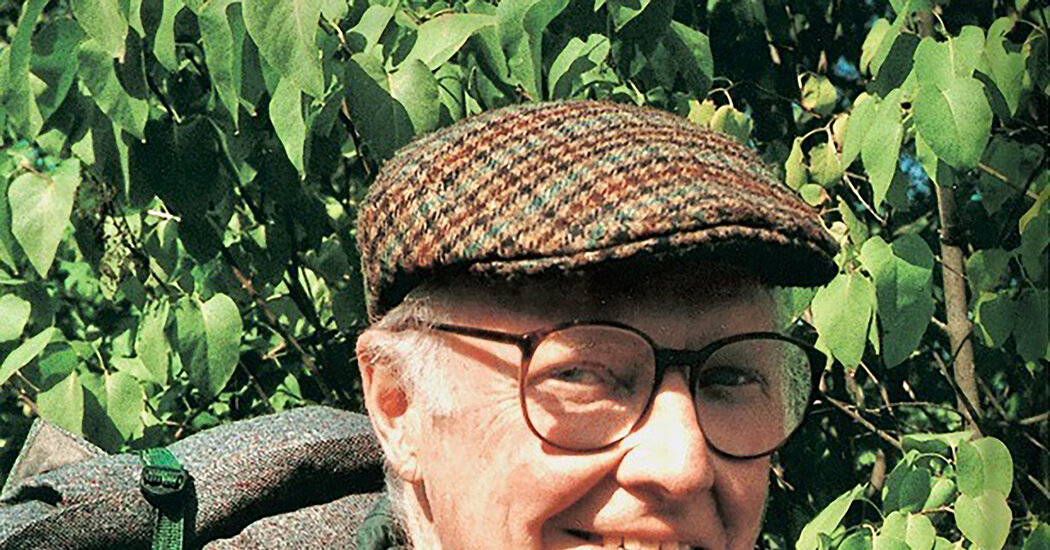

Robert E. Ginna Jr., a founding editor of People magazine, a book editor and a film producer whose 1952 Life magazine article provoked a frenzy by validating the idea that flying saucers might exist and could have visited Earth from outer space, died on March 4 at his home in Sag Harbor, N.Y.

His death was confirmed by his son, Peter St. John Ginna. He was 99.

Mr. Ginna (pronounced gun-NAY) enjoyed a wide-ranging, eight-decade career. As the editor in chief of Little, Brown, he persuaded the acclaimed novelist James Salter to shift from screenplays to books and discovered Dr. Robin Cook as an author of thrillers. He also produced movies and was part of the team that started People as a highbrow showcase for profiles of cultural figures like Graham Greene and Vladimir Nabokov, but quit when the magazine descended into what he viewed as celebrity fluff.

To the general public, though, he was perhaps best known for an article he wrote with H.B. Darrach Jr. for the April 7, 1952, issue of Life magazine. The cover featured an alluring photograph of Marilyn Monroe under the headline “There Is a Case for Interplanetary Saucers.”

To Mr. Ginna’s eternal dismay, the article made him a target for U.F.O. buffs and kooks. Headlined “Have We Visitors From Space?,” it examined 10 reports of unidentified flying object sightings, followed by an unequivocal assessment from the German rocket expert Walther Riedel: “I am completely convinced that they have an out-of-world basis.”

While reports of U.F.O.s in the late 1940s were often trivialized, Phillip J. Hutchison and Herbert J. Strentz wrote in American Journalism in 2019: “By the early 1950s, however, more substantial human-interest features embraced the idea that U.F.O. reports might correspond to extraterrestrial Earth visitors. A widely cited April 7, 1952, Life magazine feature titled ‘Have We Visitors From Space?’ represents one of the most influential examples of the latter trend.”

Capt. Edward J. Ruppelt, who led the Air Force’s internal U.F.O. investigation, Project Blue Book, wrote in “The Report on Unidentified Flying Objects” in 1956 that “the Life article undoubtedly threw a harder punch at the American public than any other U.F.O. article ever written.”

Other reporters had visited the Air Technical Intelligence Center (now the National Air and Space Intelligence Center), in Dayton, Ohio, he wrote, but “for some reason the name LIFE, the prospects of a feature story, and the feeling that this Bob Ginna was going to ask questions caused sweat to flow at ATIC.”

“Life didn’t say that the U.F.O.s were from outer space; it just said maybe,” he added. “But to back up this ‘maybe,’ it had quotes from some famous people,” including Dr. Riedel. (In 2024, a congressionally mandated Pentagon report concluded that there was no evidence that any U.F.O. sightings represented alien visits.)

Throughout his career, Mr. Ginna “carved his own path,” Jeremy Gerard, a critic, biographer and former reporter for The New York Times, said in an email.

He “quoted Yeats and O’Casey” and “valued his correspondences with many of the great writers of his time,” Mr. Gerard noted, and he wasn’t afraid to go his own way, “leaving People when its direction didn’t please him, devoting himself to teaching when the literary world was changing at warp speed, worshiping at the altar of the written word.”

Robert Emmett Ginna Jr. was born on Dec. 3, 1925, in Brooklyn. He was named for the Irish patriot Robert Emmet, as was his father, an electrical engineer who became the chairman of Rochester Gas and Electric. His mother, Margaret (McCall) Ginna, was the daughter of Irish immigrants.

In addition to his son, Peter, an editor and writer, he is survived by his daughter, Mary Frances Williams Ginna; a sister, Margretta Michie; two grandchildren; and a great-grandson. His wife, Margaret (Williams) Ginna, died in 2004. His first marriage, to Patricia Ellis, ended in divorce; they had no children. After his wife’s death, he was the companion of the journalist Gail Sheehy, who died in 2020.

After graduating from the Aquinas Institute of Rochester, he enrolled at Harvard College, but dropped out to join the Navy when he was 17 and served in the Pacific during World War II. He graduated from the University of Rochester in 1948.

Mr. Ginna envisioned a career in medical research and was already working in a laboratory when, traveling in France, he was struck by what he described as an epiphany as he gazed at one of the rose windows at the cathedral in Chartres. He returned home and changed direction, earning a master’s degree in art history at Harvard and working briefly as a curator of painting and sculpture at the Newark Museum of Art.

Later in his 20s, Mr. Ginna was a freelance writer for the Gannett group of newspapers before joining Life in 1950. His interview of the Irish dramatist Sean O’Casey for NBC would inspire him to produce a film called “Young Cassidy” (1965), based on Mr. O’Casey’s memoir. (Sean Connery was supposed to star, but opted to play James Bond instead.)

Mr. Ginna also produced “Before Winter Comes” (1969), starring David Niven, Anna Karina, John Hurt and the Israeli actor Topol, and “Brotherly Love” (1970), starring Peter O’Toole and Susannah York.

“As a producer, Ginna may have had limitations,” Mr. Salter wrote of their Hollywood misadventures in his memoir, “Burning the Days” (1997). “He was scrupulously honest. He was a classicist — his interests were cultural, his knowledge large — and unequivocal in his statements and beliefs.”

After working at People, where he was a founding editor in 1974, he went on to serve as editor in chief of Little, Brown from 1977 to 1980, his son said. There, he published “Coma,” the first medical thriller by Dr. Cook. He then briefly returned to Time Inc., which was trying to revive Life. Beginning in 1987, he taught writing and film at Harvard University. He took his final publishing job at 80, starting an academic press at New England College, in Henniker, N.H.

When Mr. Ginna was in his early 70s, he traversed the length of Ireland, lugging a 38-pound rucksack, a journey he recounted in “The Irish Way: A Walk Through Ireland’s Past and Present” (2003). In 2016, at 90, he retired from teaching but continued to write. He left an uncompleted memoir titled “Epiphanies.”